|

IT IS DIFFICULT to be completely objective

about the DS-19. The car is almost too

fascinating. Not even the most unimpressionable

automotive analyst could concentrate long on any

weak points when confronted with such an array

of automatic gadgetry. But gadgets per se count

for little in our book when they are merely

extra-cost contrivances tacked on to catch the

public eye or compensate for poor design, That

is why the automatic devices on the Citroën are

of special interest‚ they are each an integral

part of a new design concept intended to reduce

driver effort to an absolute minimum. Their

success is not entirely unqualified, but the car

as a whole is a brave and estimable effort to

break the fetters of convention and give the

public something safe and comfortable in

transportation.

When we picked up the test car at Citroën Cars

Corporation in Beverly Hills, we received a

half-hour of essential “checking-out"

instruction by the distributor, and it would

appear that such a familiarization course is

going to have to be standard procedure with

every customer. Not that this is bad - it just

takes a while to get used to a car that has no

springs, brake or clutch pedals, and moves up

and down as though it had a life of its own.

First comes a course in tire changing. The spare

wheel, tools, and jacking stand are kept up

front under the hood, but very little physical

effort is required to make the switch. A few

seconds after starting the engine, pressure is

built up in the hydraulic system, the body

rises, levels, and assumes its normal riding

position. The ride control lever is moved as far

up as it will go, whereupon the body ascends

even farther away from its wheels (this position

can also be used to increase ground clearance

when driving over deeply rutted roads). Now;

with metal stand hooked on a fitting under the

front door, the ride control lever is moved to

extreme down position, and since the body,

supported by the stand cannot sink, the two

wheels on that side rise off the ground, and

either can be removed by unscrewing a single

central nut instead of the usual multiple lugs.

In the case of a rear wheel, the rear fender

panel must also be removed, another simple,

single-nut operation. With new wheel in place,

the car is lowered by reversing the first

procedure and the driver is off having expended

less than half the time and energy of a

conventional tire change.

|

|

Next in checkout comes driver controls. Near

the accelerator pedal is a small, rubber-covered

button that suggests a headlight dimmer switch;

it operates the brakes (inboard discs in front,

10 in. drums in rear) but has a travel of barely

half an inch. Applying the brakes, therefore,

becomes a matter of foot pressure rather than

movement and can easily be overdone at first. To

the left there is also a pendant pedal for the

emergency parking brake which operates the front

discs by a separate system and can actually be

used to stop the car from cruising speed. There

is no clutch pedal. The steering wheel is

supported by a single column/spoke that bends to

the left out of the dash and joins the rim at

one point only. This is intended as a safety

feature, the idea being that in a collision,

with wheels straight ahead, the steering wheel

will yield on its unsupported (right) side

throwing the driver into or under the dash all

of which is made of crash-yielding plastic.

Between steering wheel and dash is located the

gear-shift lever which operates in three

vertical planes: the plane closest to the dash

contains low and reverse: the plane closest to

the steering wheel contains 2nd, 3rd, and 4th

(an overdrive); the center plane is neutral, but

by pushing the lever far to the left, the

starter is actuated. Besides the usual dash

instruments and controls, there is also provided

a warning light to indicate lack of brake

pressure, a manual spark control, and an

auxiliary clutch control to engage the clutch

for hillside parking, since it automatically

disengages when the engine is off.

Final item in checkout is correct gear-shifting

technique. The clutch is automatically

disengaged when 1) engine revs drop to idling

speed and/or 2) the gear shift lever is moved.

To start from a standstill, the accelerator is

depressed engaging the clutch, and severity of

depression governs smoothness of engagement.

Shifting is accomplished manually with much the

same coordination of accelerator/shift-lever

movement as though there were actually a clutch

pedal. All these instructions sound a good deal

more complicated when described orally or on

paper, hut most aspects of the car’s operation

come fairly easily when you are in the driver's

seat.

Once underway on our own in Los Angeles traffic

with the DS-19, we experienced a few moments of

panic as feet instinctively flailed for pedals

that weren’t there, hut soon things quieted down

on the freeway, and finally at the testing strip

we began to make friends with the car. As can be

seen from the photos, it is striking looking but

clean and not unpleasing. The low, Studebakerish

snout slopes up to an enormous curved windshield

with spider-thin posts.

An amazing 123-in. wheelbase (to an overall

length of 189 in.) is achieved by placing the

rear wheels so far back that overhang is almost

eliminated. They are also 7 3/4 in. closer

together than the front wheels, which apparently

caused a well-meaning elderly couple in a Ford

to blast up alongside us on the highway and warn

us that our car was “way out of line—no rubber

when you get there, Bub!” Inside, there is

comfort galore for five. Foam rubber is used

lavishly in the soft, relaxing seats, under the

floor mats, around the roof edges, on the sun

visors and armrests — and insulation from noise

is its by-product. With the 17-gal. gas tank

located under the rear seat, there is room for

17.5 cu. ft. of uncluttered space in the deep

trunk. On every kind of surface traversable by

four wheels the “hydropneumatic” suspension

fulfils its designers’ claims by absorbing shock

and maintaining stability to a degree never

before achieved. Cornering is extremely flat, and

hardly a sound comes out of the Michelin “X”

standard equipment tires. And strangest of all

is the eerie presence of the hydraulic leveling

device, quietly adjusting and readjusting for

the slightest shifts, additions, or removals of

weight.

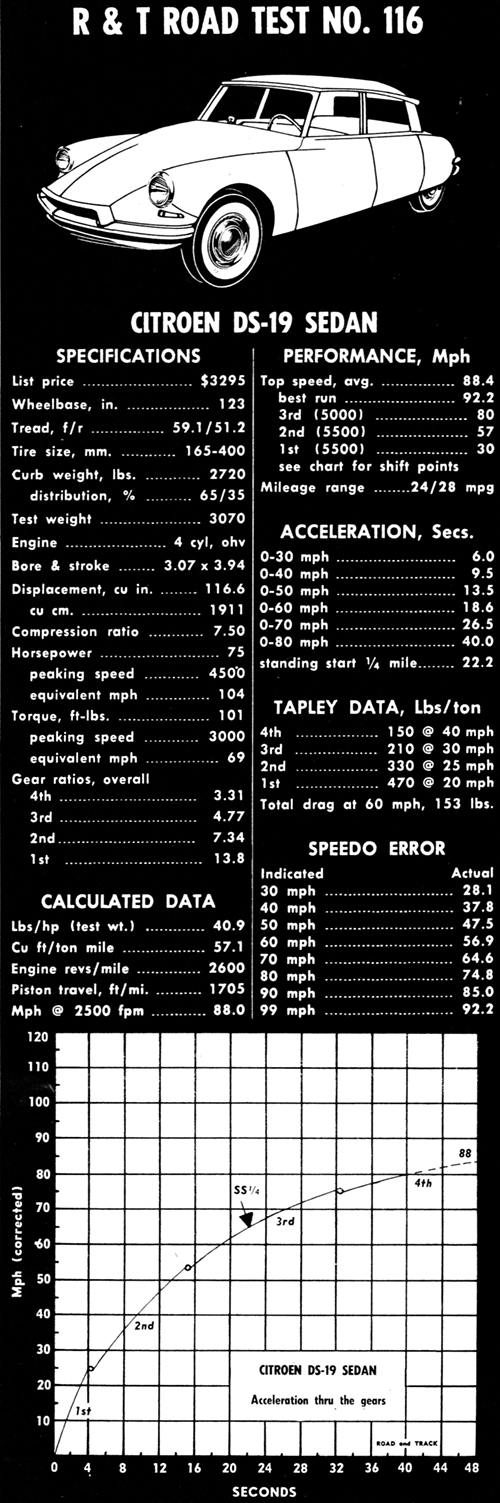

In the acceleration tests, gear shifting proved

no problem, but neither did the system lend

itself to optimum times. Performance in all

gears was adequate, though less than sparkling,

and fourth is strictly for economical highway

cruising. Overall mileage for the test averaged

24.3 mpg, and on a long, easy trip 30 mpg is not

out of the question. The power brakes proved

enormously effective, and there were no

complaints about the power-assisted

rack-and-pinion steering, although it was by no

means finger-light in parking. Best top speed run

was just over 90 mph, and both car control and

normal-toned conversation were as easy as at 50.

What are the drawbacks of a car so obviously

ahead of its contemporaries? As one U. S.

designer put it, “We could build the system into

our cars, but it’s putting all your eggs in one

basket.” If the hydraulic power fails, the car

is largely incapacitated, although there is

enough pressure in the “accumulators” to keep

things going for a bit. The hydraulic fluid

reservoir holds 11 pints, but in the intricate

network of pipes, tubes, and valves, there is

the ever-present danger of dirt, leaks, etc. And

the thought of repairs in case of heavy damage

is staggering.

Even so, the Citroën DS-19 (“D” for Désirée,

“S” for Speciale, and “19” for 1911cc) is no

mere precocious dream car; it is a production

automobile available for a little over $3000 and

as such, a memorable motoring milestone. We

found the car thoroughly likable, and our only

serious question is: with all the automatic

features of the car, why wasn’t some form of

fully automatic transmission provided, thus

eliminating the one item requiring most

familiarization?

|

|