|

THE MOST COMFORTABLE SMALL CAR in the world, people

said. Others went further: the best small car of all (well, that or the

Alfasud). Certainly the CitroŽn GS in its early years was the most

aerodynamic the most technically advanced, the purest in design and the

most distinctive. But that was all a terribly long time ago. Now, after

an interregnum of six years since the last GSAs. CitroŽn is back with

the ZX, a new car to sit in size and price between the AX and BX,

embodying what is, for the company, new thinking.

The ZX, in direct contrast to the GS, is calculatedly conventional.

It’s a rather dull-looking five-door hatch powered by a four-cylinder

transverse in-line water-cooled engine, its front wheels driven via an

end-on gearbox, suspended on steel-sprung MacPherson struts, and its

rear axle on trailing arms. Brakes are servo-assisted, using discs and

drums on this basic 1360cc Reflex model. So what's new? Chiefly, a rear

subframe mounted on bushes that deform in a shrewdly designed way

during high sideways load, causing the rear wheels to turn slightly in

the same direction as the front pair to improve cornering stability.

It’s worth boasting about, and it works, but it's not unique. Also,

some ZX models - but not this one - have a sliding and reclining rear

seat, novel for a European car.

The GS has a four-door fastback body of remarkable aerodynamic

efficiency, and a longitudinally mounted air/oil-cooled flat-four ahead

of the front wheels. Front suspension is by double wishbones, rear by

trailing arms, with interconnected self-levelling hydropneumatic

springing/damping units at each corner. The high-pressure hydraulics

also power the all-disc brakes, inboard at the front. There are more

surprises: the steering axis passes exactly through the tyres’ contact

patches so that the car continues in a straight line after a front tyre

blow-out, there is a remarkable degree of anti-dive provided by the

suspension geometry, and the rear brakes are pressurised by the rear

suspension fluid so that their action is proportional to the car's load.

The GS tested here isn't quite like they were two decades ago. The GS

first came with engines of 1015cc and 1222cc, designed with an eye to

French taxation rather than performance. They were astonishingly

high-revving, short-legged cars. This GS is the later X3 model

introduced in 1978, its engine expanded to 1299cc in an attempt to help

the 65bhp engine's torque and economy. It's still short-geared:15.4mph

per 1000mph in top (fourth) means a 5500rpm motorway cruise is possible

but deafening. But, apart from the bigger engine, the revised rear

lamps and the ghastly seat trim, the X3 is as the GS was at the outset.

This car is owned half-and-half by me and deputy editor Richard

Bremner, and we didn't set out looking for an X3 — we just wanted to

buy a well-preserved GS of almost any description before they all

rotted away.

Start up, and you know you're in something unconventional. it's not

just the absence of water temperature gauge that points to the cooling

method: there being no sound-absorbing liquid jacket, this is one loud

engine. But it's a nice sound, remarkably like a pair of 2CVs or, if

you prefer (and l do), two-thirds of a 911. Horizontally opposed

engines, all of them, have a lovely soft-edged sound that rises in

pitch and volume higher up the rev range while avoiding any harshness.

They sound as though they'll never break.

|

|

|

|

|

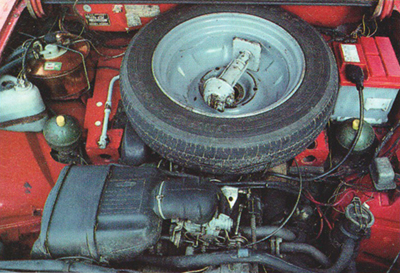

Performance of G5 (top) and ZX is similar,

new car’s greater torque offset by longer gearing.

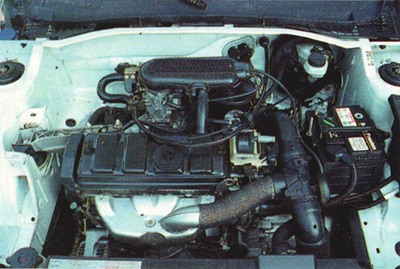

ZX cleaves air

quietly. Tyre noise. too, is well suppressed. GS falls down on

refinement: it suffers noise from wind, tyres and engine. GS has a

longitudinal 1299cc air-cooled flat four, ZX 1360cc transverse

water-cooled in-line four

|

|

|

|

The ZX's engine, though a deal quieter in the middle

ranges, isn't so

nice to use as it turns rough when you push it, so you adopt a

different technique when trying to get along briskly, using higher

gears (you've five to choose from) and lower crank speeds. Performance

of the two cars is very similar, the ZX's greater torque of 85lb ft

against 72lb ft being offset by slightly longer gearing, while both

cars weigh 19.5cwt.

Its uncouth engine apart, the ZX is clearly ahead of the 1991 class

standard for refinement. It cleaves the air quietly, even though its

drag coefficient, at 0.32, certainly doesn't reflect two decades’

progress from the GS's 0.34. Tyre noise is very well suppressed.

There's no steering kickback or transmission shunt, and the gearshift

has a light, clean-slicing action. It's an easy car to drive.

It's leagues ahead of the GS in refinement. The old car falls down

badly here - by far its biggest drawback on the road. Beyond 70mph, the

wind whips up a cyclone roar, accompanied by bad tyre noise and a

shriek from the gears, yet still the engine's voice is strident enough

to be heard above the cacophony. The gearchange is light and quick, but

hasn't had the rough edge taken out of its action, and there's enough

backlash in the driveline to demand great circumspection from the

driver coming on and off the throttle.

Two decades have seen ergonomics move forward, of course. The GS dash

is a right mess, and badly made with it. But the car's driving position

is fine, and slim pillars impart airiness and visibility. The ZX

counters with easily found, illuminated switchgear and proper modern

heating and ventilation, where the GS has a weak-willed set-up directed

by a scattered set of levers that sprout from roughly carved gashes in

the frangible plastic facia.

CitroŽn badly wants the ZX to appear well made, and it does.

Although

the company's claim that it's the best in its class represents a

combination of innocent naivety and cynical marketing hype (the seat

trim and dash are of cheapo materials), the fact is the facia

components all fit well, the heater dials turn smoothly, the glass is

neatly semi-flush and the metal panels are thick and well fitting. More

important, the fact that the body doesn't boom and crash over bumps is

a great step forward for CitroŽn.

In the GS, you hear bumps, and feel them through the steering wheel.

There's also some harshness over small, sharp bumps such as Catseyes.

But real lumps, undulations, pot-holes, cobbles and broken surfaces are

simply swallowed. No car today— up to limousine size - is so soft, and

yet the GS seldom floats. To the owner of a backside accustomed to the

jarring rides of modern small cars, it's amazing. On top of which, the

car is unaffected by load.

By modern standards, the ZX rides well. It is resilient, moving up and

down but taking the edge off things well. There’s none of the lurching

and thumping a German car would serve up on lumpy French roads. Its big

fault is an uncomfortable lateral rocking, brought about because the

car, though softly sprung, is quite stiff in roll. Anti-roll bars are

simply lateral springs, and undamped ones at that, so when one side of

the ZX is disturbed the whole thing rocks. The GS, like the ZX, has

anti-roll bars at each end, hut they are far less influential.

Ride quality, though, is but one element in the sum of comfort. Both

cars have soft, generous seats, good driving positions and adequate

cabin room. The GS has better rear-seat headroom, the ZX the better

legroom, though for back-seat roominess, it's shamed by the Tipo.

In packaging, the two CitroŽns are remarkably similar. The ZX is 160in

overall, the GS two inches longer, the wheelbases are the same, the

heights similar, yet the GS has the bigger boot by 45 percent when the

ZX’s rear seat is up.

No progress there in 20 years. But surely all this softness in the GS

must make it handle like an inebriate camel? Not a bit of it. Sure, it

rolls onto its door handles, but it clings on amazingly well with its

round-shouldered tyres, understeering insistently at the limit.

There's excellent directional stability yet neat turn-in: the steering

is very direct and accurate, though you pay a price in having to put up

with kickback and a marked weighting-up in bends. The GS‘s big 15-inch

wheels help the ride and give a reasonably big contact patch from

145-section tyres.

The ZX rolls less, as it must in order properly to exploit modern

lower-profile 165/70 13 tyres. Drive the ZX’s contemporaries and you'd

call its steering light, quick and accurate, but after the GS‘s it

feels a tad rubbery, which must be the pay-off for losing the kickback.

Still, the ZX turns into bends eagerly enough, and then brings its

self-steering axle into play by tracking around the arc with remarkable

tenacity and even-handedness — tucking in only gently even when you

throttle right back – and gripping very strongly. Its two-stage

cornering action feels odd at first, but you soon learn to like it — a

real CitroŽn characteristic, you might say.

The ZX doesn't have real CitroŽn brakes; the GS does, and is the better

for it. On almost no pedal travel, the GS discs have sharply honed

initial bite, great power and perfect progression, aided by the car's

remarkable resistance to front-end dive. Their high-pressure hydraulics

can also be cheaply adapted to ABS, and have been on the BX and XM. The

ZX’s stoppers work well enough but feel spongy beside conventional

opposition's and especially so beside the GS's.

So just what does CitroŽn have to show for 20 years‘ developments? To

look at, drive or sit in the two cars here, you'd be hard put to find

much beyond the refinement angle. But look at the costs.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

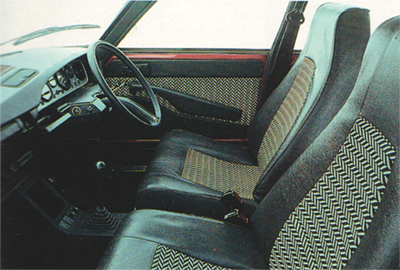

Soft suspension has GS (top left) rolling

around bends, but it holds

road well. ZX turns in eagerly, corners

evenhandedly. Rear seats are soft and

generous in

both cars, their cloth trim showing CitroŽn hasn't lost its taste for garish

colour. GS has switches

scattered over Its messy clash. ZX's facia is neater —has better ventilation

(above)

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

In

its youth, GS was most distinctlve car around, and the most

aerodynamic. Its 0.34 Cd compares well wlth ZX's 0.32. New car's design

is calculatedly conventional. Both cars have good driving positions and

adequate cabin room. Not only ls GS’s dash a mess, it’s also badly

made. ZX’s facia (above) is blander but better to use

|

|

|

|

The GS's 27 to 32mpg isn't too clever when you’d be

doing nearer 40 in

the ZX, and an early GS's 3000-mile service interval would horrify a

1991 owner. A GS would need 30-odd hours‘ servicing in its first 60,000

miles whereas this ZX gets by on 5.5 hours plus oil-changes. You'd

swear maintenance wasn't given a second thought when they designed the

GS - the distributor is so badly sited you need to remove it to

check

the points – yet the BX proves that with modern design, electronic

ignition and today's lubricants, the care of a hydropneumatic car

needn't be a problem.

The GS is reliable if cared for, and mechanically durable, but in damp,

salty Britain its body disappears like April snow. TheZX is carefully

designed to eliminate rust—traps, and 75 percent of its steel is

galvanised or electro-plated. It should last well and when it's done

for, its constituent parts will be labelled for recycling.

The ZX is strong, having a very rigid floor and three

hoops over the

cabin for stiffness and rollover protection. It is claimed to be safe

in 35mph frontal impacts where the law demands 30mph, and to deal with

offset crashes, too, for which there is no legislation. The GS isn't

bad in its crash resistance. but the ZX is better. Yet in primary

safety, the ability to avoid the crunch, the GS lags little.

‘I can’t imagine,’ said someone from CitroŽn at the ZX‘s launch, ‘that

anyone who drives our car will have anything to complain about.’ Well

I, for one, will grumble. However good the ZX may be (and it is very

good), it's not a car to hold your interest. As far as CitroŽn is

concerned, it's hardly a car at all. It's a product, an appliance,

carefully tailored to existing consumer demand in market segment Mi.

The buyers know what they like, and CitroŽn has inferred that they like

only what they know. So the ZX is just what they know, a little better

all round, but no different. It is, in short, a marginally improved

competitor to Bland X.

CitroŽn makes cars to make money, and we can't blame it. There's only

sense in building something different if it can be economically made

and abundantly sold. The danger the ZX faces is its perilously short

potential lifespan: before long there’ll be a new Golf, a new Astra, a

new 309, several new Japanese, and any or all of these could well

better the ZX, leaving CitroŽn floundering for a replacement.

The GS, by being different, has qualities that haven't been bettered in

20 years, and perhaps never will be. Its faults are evident and

manifold: it is unrefined to drive and, though reliable, is extravagant

in its demands for fuel, care and attention. But all of these could

surely be cured by modern design and engineering, without abandoning

hydropneumatic systems, adventurous styling and sophisticated (though

not necessarily complex — the GS isn't complex) engineering. The very

thought of it all makes the ZX seem like a wasted opportunity.

Paul Horrell

|

|

This was one of four

articles in this issue comparing then current models with their

predecessors from twenty years previously. The other

comparisons were Jaguar XJs with E-Type, Audi 100 with NSU Ro80 and

Alfa 33 4WD with Alfasud.

These are the conclusions:

Cost

WE'RE PAYING A LOT MORE FOR OUR CARS now than we did 20 years ago, once

you take inflation into account.

Example: in 1971, an Escort 13O0XL cost £1004 including tax, whereas

today's Escort 1.4LX is £10,125. In the meantime, the Retail Price

Index has risen so that £1.00 in 1971 would buy what £6.74 buys now.

Thus you might expect today's Escort to cost just £6767.

Similar figures apply pretty well right across the spectrum. In '71, a

Jaguar XJ6 4.2 auto was £2969; multiply that by 6.74 and you'd expect

to pay £20,011. Instead, Jaguar asks £29,880 for an XJ6 4.0 auto. The

table gives more examples of then-and-now prices; in each case, there's

a gap between what inflation would lead you to expect to pay, and the

actual price now ~ and sometimes it's a chasm: an Austin 1800 (£1246)

points to a price for a base Rover 820i of £8398 not the actual £17,181.

Don't imagine the recent VAT increase signals an overall rise in tax.

In 1971, you paid 30.7 percent purchase tax; now, it's roughly 8.0

percent special car tax (actually 10 percent of wholesale price) with

17.5 percent on top, amounting to 26.9 percent in all.

Car makers would have you believe labour costs have gone through the

roof, but in fact Ford's line workers were paid 75.5p an hour in '71 ;

now they average £5.89 - only a small real increase. And Ford in

Britain turns out roughly twice as many cars per employee now as it did

then.

Perhaps greater sophistication and better equipment could justify

higher prices. Our pair of Escorts again: the difference between the

expected price extrapolated from '71 and the actual '91 price is £3358.

What do you get for it? In '71 you suffered a pushrod motor and

cart-sprung live rear axle, and you paid extra for servo-assisted front

disc brakes, cloth seat trim, a heated rear window, radial tyres and

AM-only radio. Today's 1.4LX - which has all-independent suspension, a

five-speed gearbox and an ohc engine – includes as standard an array of

goodies the '71 car had to do without: halogen headlamps, sunroof,

electric front windows, rear foglamps, intermittent wipe, rear wiper,

door mirrors, locking fuel filler, side window demisting, reclining

seats, clock, tripmeter, stereo radio-cassette player, hazard flashers,

boot light and burglar alarm. An impressive list, but is it worth £3358?

Styling, Engineering

OVER THE PAST TWO DECADES, THE choice available to buyers has been

lamentably narrowed. We've already examined (CAR, July 1990) the way in

which cars are looking more and more alike – a trend that's not

convincingly justified by the demands of their aerodynamics or safety.

The real reason could be called prudence or cowardice: manufacturers

simply refuse to build adventurous designs in case they turn out heroic

failures, opting instead for the safe course of building near-clones of

what's already selling well.

Under the sheetmetal, the convergence between manufacturers is even

clearer. Certainly, the transverse engine is good for interior space,

and front-drive bestows both roominess and predictable handling, the

coil-sprung MacPherson strut is cheap to make and compact. But is this

really such a magic formula? In the '70s, we were offered particular

engineering solutions to particular problems; nowadays every car's much

the same. In 1971, Fiat sold the rear-engined 850, the front-engined,

front-drive 127 and 128, the rear-engined, rear-drive 124 and 132, and

the V6 130. The X1/9 and 126 followed in '72. Now, there's little

fundamental variation in engineering from the upcoming

Cinquecento microcar through the Panda, Uno, Tipo and Croma -taking in

the Lancias Y1O, Dedra and Thema on the way. In '71, Lancia offered

narrow-angle V engines, flat-fours, transverse leaf suspension, and

coachbuilt coupťs.

There are some modern exceptions to this oppressive conformity. The

Metro’s fluidsuspension; the Renault Espace's space utilisation and

unique body construction; the Lotus Elan's bold styling and clever

front-drive engineering; the Citroen XM's step-ahead suspension; the

Honda NSX’s radical aluminium construction; the Audi Quattro’s

four-wheel drive — none of these features has hampered sales success.

Detail engineering has moved on, of course. We now have widespread fuel

injection, electronic ignition, ABS, turbos, better bumpers, flush

glazing, rear-wheel steering (whether active as with Honda, Mazda and

Nissan, or passive as with Porsche, VW and CitroŽn), better auto

gearboxes and smoother diesels. But revolutions have been too few, we

think.

Performance, Economy

THE TABLE GIVES EXAMPLES: IN GENERAL, comparable cars are faster now,

and a little more economical. Performance is no longer the preserve of

the few, either; an Astra GTE 16-valve of '91 performs near-identically

to 1971's 4.2-litre E-type.

Yet no-one could say performance and economy have leapt ahead. The

motivation to improve economy hasn't really been there, in that a 1971

gallon of four-star cost 35p including taxes, which would be an

inflation-corrected £2.36. So fuel is cheaper now than it was, and the

trend has been for us to choose to drive faster in quicker, heavier

cars.

Engine efficiency has barely risen. For mass-market 1.0 to 1.6-litre

engines, power output per litre has risen by just 10 percent or so in

most cases. Expect no improvement over the next few years, either:

catalytic converters will see to that.

Most consistent improvement has been in top speed, and in design for

relaxed and economical motorway cruising. This has a lot to do with

aerodynamics and the fall in from, say, 04.5-0.50 then to 0.30-0.35

now. But aerodynamic drag matters only from 50mph-odd upwards, and

doesn’t affect acceleration, or fuel used during acceleration.

Acceleration has made less progress, because of the seemingly

unstoppable trend for cars to put on weight. Again, the table shows the

figures.

Sure, the extra equipment we expect these days adds to a car's heft,

but if car makers and their computerised design aids are as clever as

they claim, they should be able to save weight elsewhere, chiefly in

the metal body of the car. With a few exceptions – the CitroŽn AX and

Honda NSX among them - that hasn’t happened.

Handling, Roadholding

IN 1971, YOU COULD BUY A FEW FRONT-wheel-drive cars that handled

predictably and safely. Now almost every car-maker builds them, for the

gap between worst and best is much narrower. And the rear-drive cars -

many of which had rude swing axles or cart-sprung live axles — now tend

to be better engineered and a lot more orderly on the road, too. But

the real enthusiasts‘ cars are perhaps little better balanced or

responsive than they were. The Lotus/Caterham Seven can still stand

proud. In roadholding, though improvement has been universal.

No question, cars grip better now than they did, and by a wide margin.

Who deserves the credit? Not really the car makers. Step forward

Pirelli, Michelin et al.

Since the first Pirelli P7-shod supercars emerged more than a decade

ago, the wide low-profile tyre has become accepted for most cars bar

the very basic, and their chassis characteristics have had to be tuned

to suit. Everything that doesn't use a beam axle or a De Dion tube has

to corner flatter to keep these wide tyres perpendicular to the road.

Hence the firm springing and stiff anti-roll bars we've become used to.

There are other unfortunate side-effects of ultra-low profile tyres.

Once they do relinquish their hold of the tarmac, they go suddenly and

you'll be travelling fast. Extrovert sideways driving is seldom on the

menu these days. Ultra-low-profile tyres tend to follow the camber of a

road, and to induce tramlining under brakes. Most noticeable of all,

because these tyres are so resistant to changing direction at parking

speed, power steering has become far more frequently specified, and

even in 1991, not every maker can build a steering servo that achieves

the happiest combination of accuracy and feedback.

High-power front-drive cars demand further compromises in suspension

design if torque steer is to be controlled. At least the Lotus Elan

offers hope here.

Steering precision hasn‘t made much headway. To insulate their cars

from harshness and road noise, today’s designers use the cheapest

solution, rubber bushings throughout the steering system. The result is

often a loss of precision - felt as rubberiness or a softness of

response in the straight-ahead - compared with the best of two decades

ago. If you doubt this, drive a Mini.

Comfort, Accommodation

DRIVE ONE OF THE MODERN CARS IN OUR back-to-back comparisons on the

preceding pages is significantly more comfortable or space-efficient

than its predecessor and they aren't freak examples. Look at the Mini,

Maxi and Austin 1800 (emphatically roomier than a Rover 800, yet two

feet shorter). And all the while, people are on average, getting taller.

Ride comfort is, at least in a conventional steel-sprung car, one half

of a compromise. The ride/handling compromise, road testers used to

call it. Now, every maker has arrived at much the same compromise of

stiff springs and thick anti-roll bars, brought about by the

developments in roadholding we’ve just discussed, and the phrase is

seldom seen. True, today’s independently sprung Escort rides better

than yesterday's cart-sprung example, but we can’t buy Renault 16s or

Austin 1100s or NSU Ro80s any more — we simply aren’t offered the

choice of a soft-riding car.

Where are the new solutions’? Active-ride prototypes have been kicking

around for a decade, but there's nothing in the showroom. There’s a

semi-active Infiniti, but you can't buy it in Britain. The Citroen XM's

chassis is ahead of the game and few other makers seem even to be

trying to catch up.

In refinement, there has been some progress. Engines are smoother,

gearboxes less reluctant (except for Fords, as a '91 Fiesta or Escort‘s

change is still a lot less slick than a rwd '71 Escort’s), clutches

smoother, wind noise better suppressed. We also get more supportive

seats these days, and improved heating and ventilation.

Buyers love gadgets, and they're getting more and more. All add to an

impression of luxury and many are undoubtedly of genuine use. But

seat, window and sunroof motors add stones of weight to a car. So do

the subframes and extra wads of sound insulation that makers are using

to defeat the noise demon, when they can't defeat it by building

fundamentally quieter mechanical organs. It's weight that saps

performance, dulls handling and increases thirst and emissions. It's

easy and cheap to add weight, clever to lose it. Car makers aren't

being clever enough.

Reliability, Servicing,

Longevity

AT LAST, SOME REAL lMPROVEMENT. If anyone says the Japanese didn't

innovate in their early years of car making, point them to the

reliability of almost every Honda, Nissan, Toyota or Mazda that ever

took to the road. Consistently made, reliable cars are the norm now,

due to improved production engineering and greater automation.

In the early '70s, cars on this island rusted out long before they wore

out. Three or four years was the norm before the first rust appeared.

Now, we have careful design to eliminate rust traps: PVC wheel-arch

liners, plastic protection, hi-tech undersealing, zinc coating, better

painting and so on, and progress has been more than satisfactory.

Servicing costs have, in real terms, tumbled. Cortina 1600s had

6000-mile intervals, Sierra 1.6s have the same. In '71, a Cortina

service averaged £29, which is an inflation-corrected £195, yet for the

Sierra today it's just £42. For a 4.2 E-type, you had to spend between

£55 and £90 at the garage every 3000 miles; for a V12 XJS it's just

£77-£150 every 7500 miles.

Safety, The Environment

IT'S THE REIGN OF THE LEGISLATOR. CAR companies are given to pleading

that they've had to put so much effort into meeting safety and

emissions laws that they've been distracted from moving ahead on other

fronts.

Well, they have made real progress here. Active safety first: extra

grip, more predictable cornering and ABS brakes play major roles. In

crashworthiness, the gains are harder to measure. European impact laws

are still a long way behind those in the States, but are tighter than

they were in the early '7Os.

On emissions, the first laws in Britain came into force in 1976, and

they have grown progressively tougher. But not until 1993 does Britain

enforce standards the Americans had back in 1983.

Modern three-way cats provide clean air, but remember, they do nothing

for fuel economy, something that has in any case not moved forward much

since '71. And every molecule of petroleum burned produces carbon

dioxide, non-toxic, but, because of the greenhouse effect, likely to be

the biggest long-term worry of all.

Car makers are taking laudable initiatives towards recycling, though

it's too soon to say what the results will be, and some eminently

recyclable materials haven't yet found widespread use — aluminium for

instance.

But we haven't seen the big advances, the ones we hoped for during the

first fuel crisis 18 years ago, in energy reduction. Cars still cost

vast amounts of energy to build and run, and it's still oil they use.

Alternative fuels and different types of engines are coming, they tell

us, but we're getting impatient.

Conclusion

CAR MAKERS HAVE GOT LAZY IN THE PAST 20 years — and that's why we

haven't seen the progress we should have done. Those great innovators

of the past — CitroŽn, Audi, Alfa, Jaguar, Lancia, Renault, Fiat,

Leyland — have played safe, unwilling or unable to be different. And

because the clever companies have gone conservative, the mainstream

makers have hardly been keen to rock the boat, either.

The greater conservatism can be attributed to the higher development

costs for new models, so that manufacturers are less willing than

before to try to do something different - for fear of an expensive

failure. It can also be blamed on the tendency for big, conservative

firms to swallow up, and expunge the quirks from, the smaller makers

(Fiat‘s buying Lancia; Peugeot's buying CitroŽn). It's cheaper for a

major maker to standardise, as much as possible, every car in its

range. The perfidious influence of marketing - which relies on

non-experts, used to today's standards, to unlock the secrets of

tomorrow - is also culpable.

But we believe there is real hope, for the next 20 years. Social and

political pressures will force car makers to innovate; if they don't do

things differently 20 years from now, they won't be in business. Such

change is good news for the average motorist, and good news for the

enthusiast, intrigued by innovative cars. Great cars of the past have

often been born from crises (the Mini, don't forget, was a direct

upshot of the Suez crisis, and the threat of massively more expensive

oil). The trouble with the '80s, one of the least innovative decades

ever in motoring, was that we all had it too easy.

|

1971

v 1991

|

YEAR

|

CAR

|

LIST

PRICE, £

|

INFLATION-

ADJUSTED PRICE

|

TOP

SPEED, MPH

|

0-60

MPH, SECONDS

|

AVERAGE

MPG

|

WEIGHT,

LB

|

1971

|

Fiat

128 1100 four-door

|

925

|

6,235

|

88

|

16.5

|

31

|

1830

|

1991

|

Fiat Tipo 1.4 Formula |

8,271

|

8,271

|

103

|

12.8

|

34

|

2090

|

1971

|

Ford

Cortina 1600 four-door

|

1,058

|

7,130

|

91

|

17.2

|

27

|

2160

|

1991

|

Ford Sierra Sapphire

1.6 Classic

|

10,207

|

10,207

|

103

|

13.6

|

31

|

2300

|

1971

|

Austin

1800 Mk 2

|

1,246

|

8,398

|

92

|

16.8

|

29

|

2625

|

1991

|

Rover 820i four-door

|

17,181

|

17,181

|

126

|

8.8

|

33

|

3020

|

1971

|

Ferrari

Daytona

|

9,909

|

66,787

|

175

|

5.5

|

13

|

2650

|

1991

|

Ferrari Testarossa

|

123,119

|

123,119

|

180

|

5.8

|

16

|

4630

|

1971

|

Rolls

Royce Silver Shadow

|

9,925

|

68,895

|

118

|

10.3

|

15

|

4630

|

1991

|

Rolls Royce Silver

Spirit 2

|

93,157

|

93,157

|

127

|

9.9

|

14

|

5180

|

|

|