|

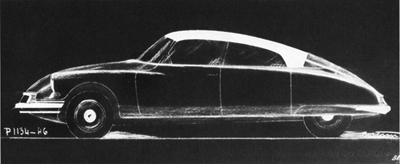

From

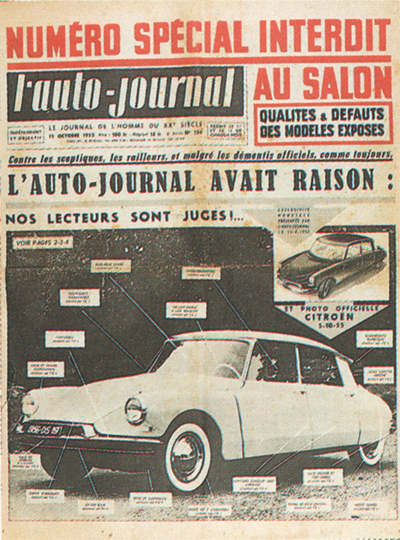

1951 onwards, prototypes were clandestinely tested on the deserted

roads

of the Midi. In April 1952, l'Auto Journal published photos of one of

these

cars. In the June edition, they published accurate technical

specifications.

Bercot was furious and called in the police but the journalists refused

to divulge their sources. CitroŽn improved security and a veil of

secrecy descended over the new car, only to be lifted slightly with a

preview

in 1953 of hydropneumatic suspension in the 15

CV H.

|

|

|

|

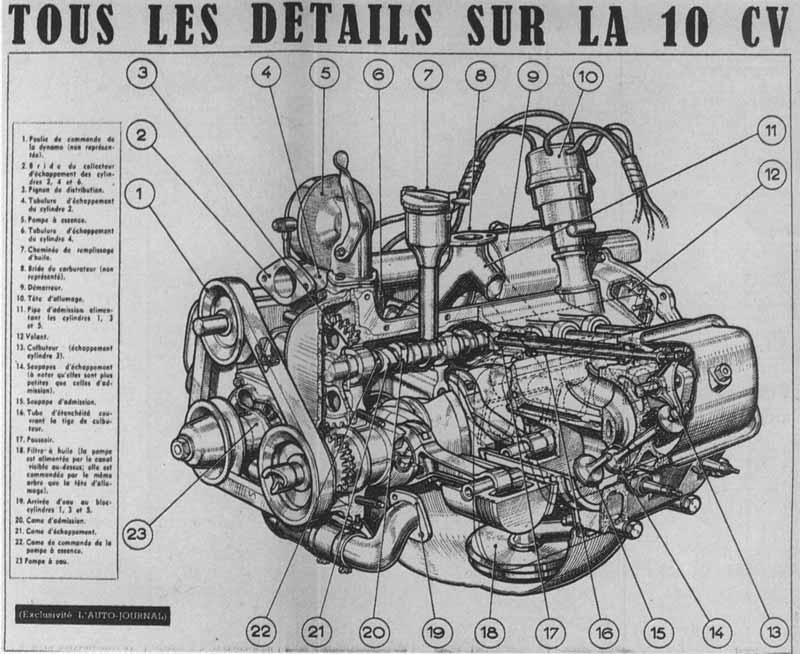

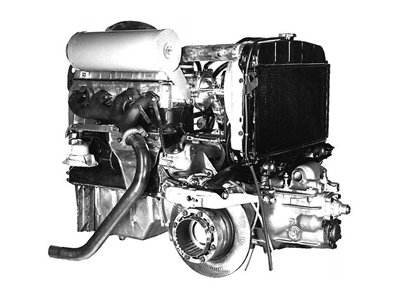

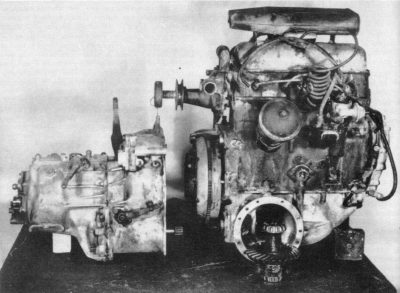

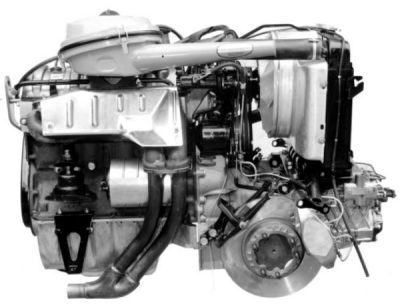

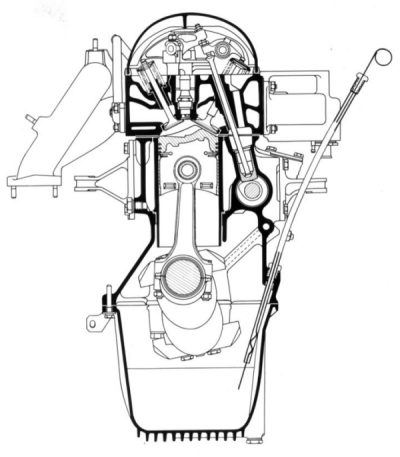

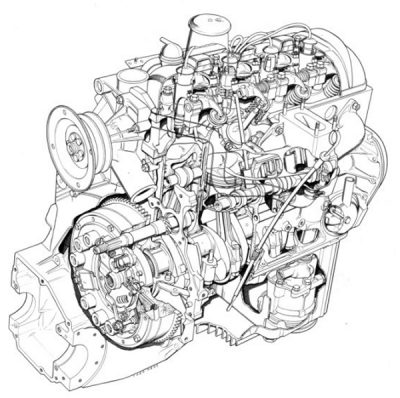

A "new" engine

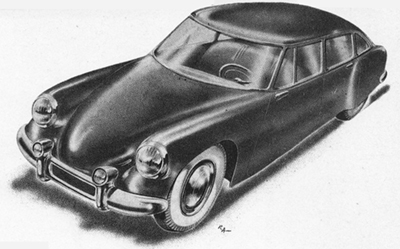

Following the abandoning of

the flat six , Georges

Sainturat,

the man responsible for designing the Traction's engine was given the

task

of redesigning that engine so it could be used in the new car. He

reworked

the cylinder head of the 1 911cc engine (the Traction six cylinder was

too long) and with various modifications managed to extract 75 bhp from

it. The "new" engine was too tall to fit in front of the gearbox so the

Traction layout was employed even though this meant that the engine

protruded

into the passenger compartment.

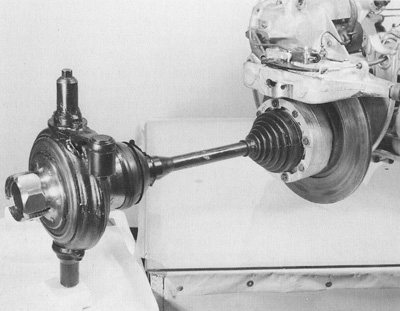

In

an attempt to ameliorate this problem, designs incorporating the

differential

inside the sump were worked on right.

This meant that the engine/transmission

assembly could be shortened but financial constraints meant that the

project

was abandoned.

|

|

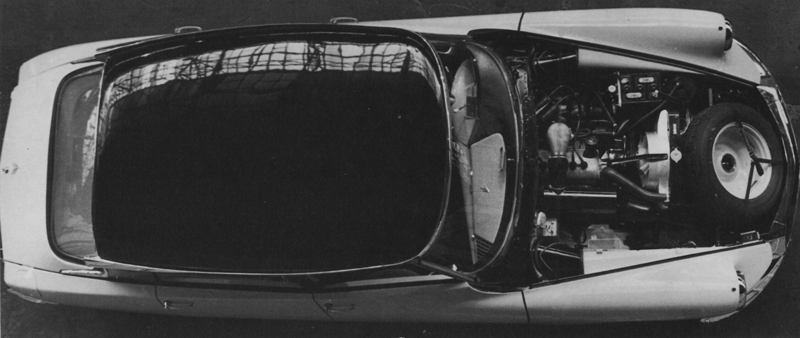

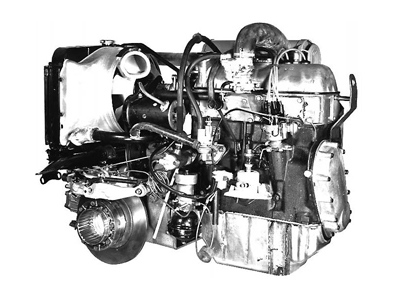

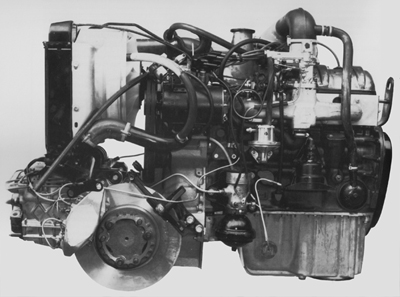

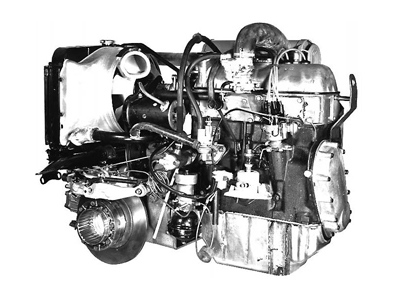

| Below - ID engine - front of the car

to the left |

|

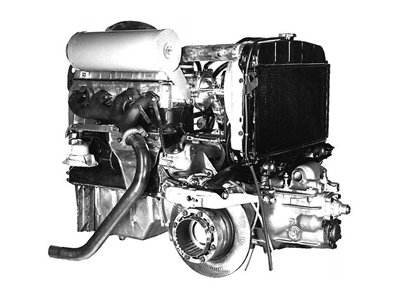

| Below - ID engine - front of the car

to the right |

|

|

|

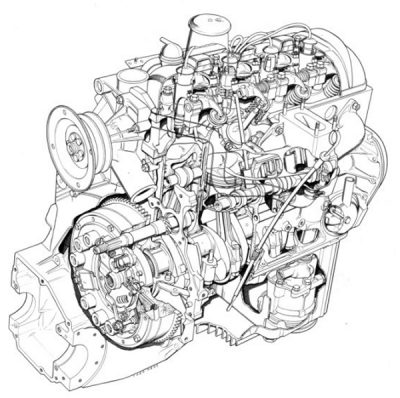

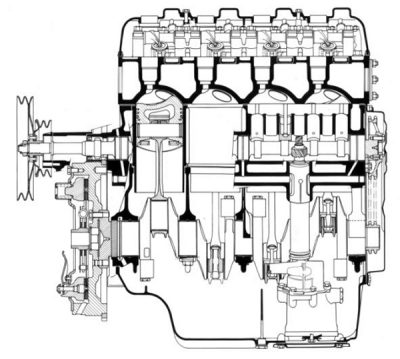

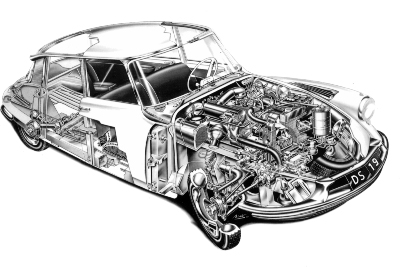

Disc brakes

Following Jaguar's

1953 win at le Mans with car equipped with Dunlop disc brakes, it was

decided to equip Projet D with front discs mounted inboard on either

side of the differential. The DS was effectively a mid-engined front

wheel drive car.

|

|

|

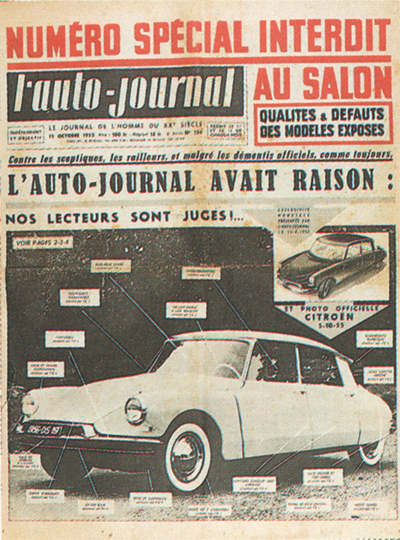

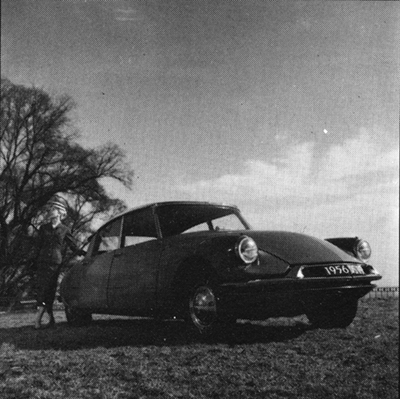

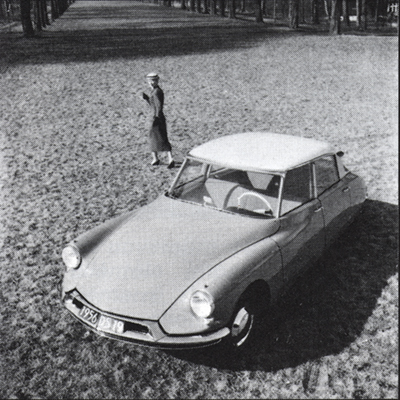

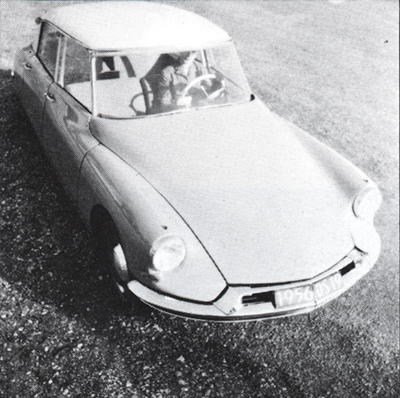

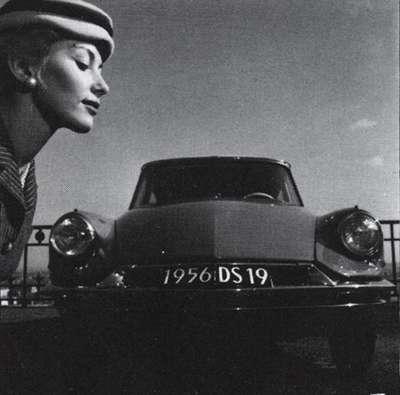

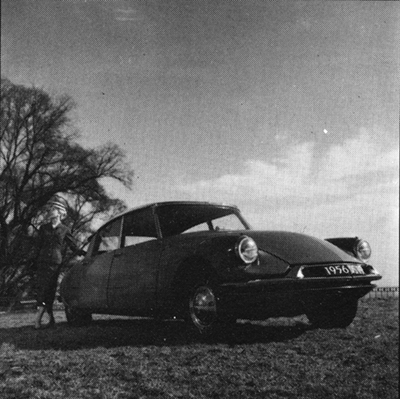

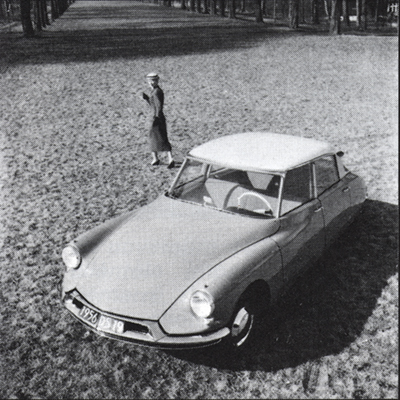

Thursday 5th

October

1955

At 9 o'clock, the

new CitroŽn was unveiled at the Paris motor show.

|

|

|

|

|

Unfortunately, so

had the problems. No-one had the faintest idea how these cars worked.

The workshops had no manuals. The salesmen had no publicity material.

The obsessive need for secrecy had worked against the company. early

cars were less than totally reliable. Many was the owner who found

himself stranded with no steering, no brakes, no

clutch, no gearchange , no suspension and a big pool of fluid under

his car. The local garagiste had no idea what to do. The

company

quickly mobilised itself, providing the agents with the necessary

workshop

manuals and training to allow it to honour its guarantees. But when it

was working, the DS was undoubtedly la Reine de la Route

offering novelty and modernism in addition to unprecedented levels of

comfort, road holding, braking and safety.

Little by little,

the bugs were solved. The hydraulic fluid formulation was improved to

reduce oxydisation caused by the intensely hygroscopic properties of

the early fluid and eventually, the DS became as reliable as any of its

conventional contemporaries - if maintained properly.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

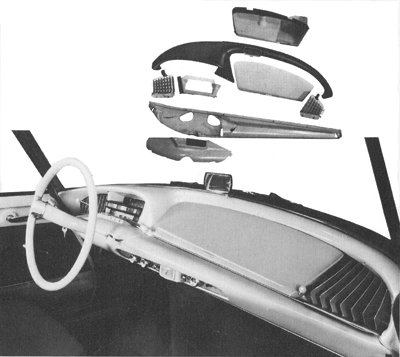

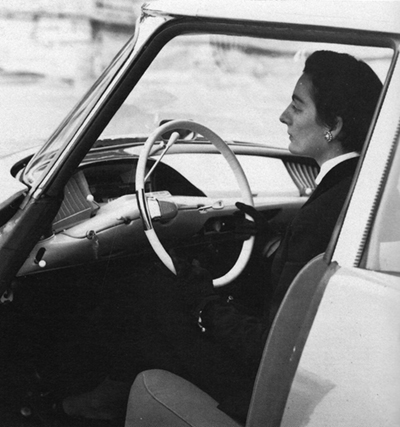

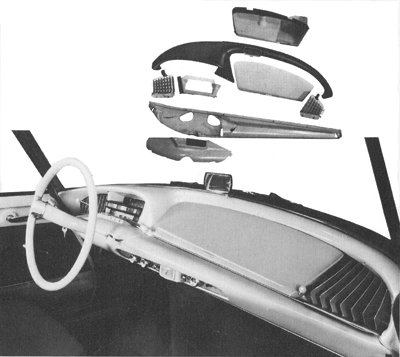

Extensive use was made of plastics - the new wonder

material

in the nineteen fifties. The futuristic dashboard was entirely made out

of plastic as was the cooling fan while the translucent roof was made

out of fibreglass.

|

|

|

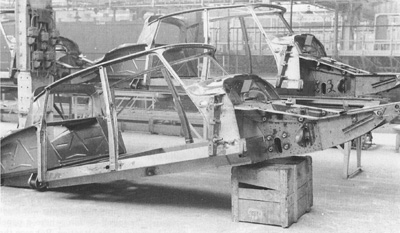

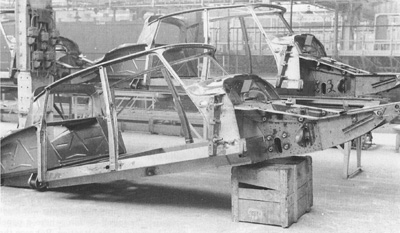

Above lightweight body panels were

bolted (or in the case of the roof, screwed) to the welded "caisson".

Right centre-point steering (where the

pivot

point passes through the centre of the point of contact between the

tyre and road surface) had been introduced on the 2CV

as had inboard brakes. Inboard brakes reduce the unsprung weight

although replacement of the pads was a labour-intensive task. Another

advantage is that cooling of the discs is better. The parking brake

operated on the front wheels.

|

|

|