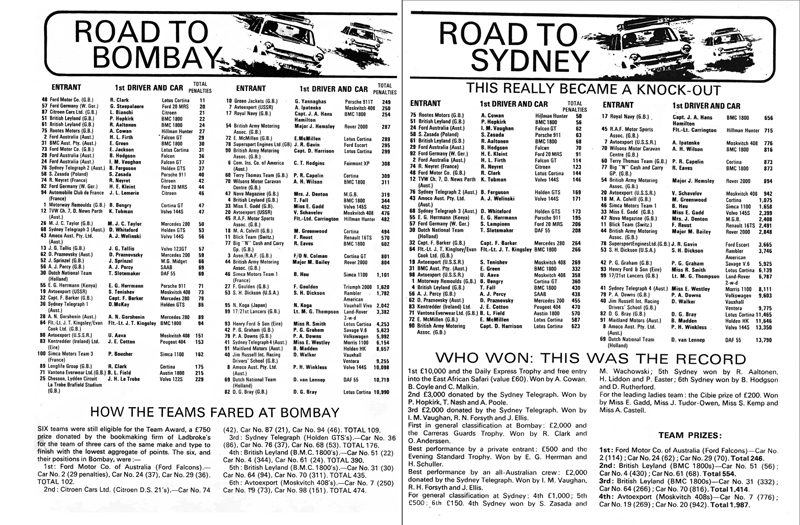

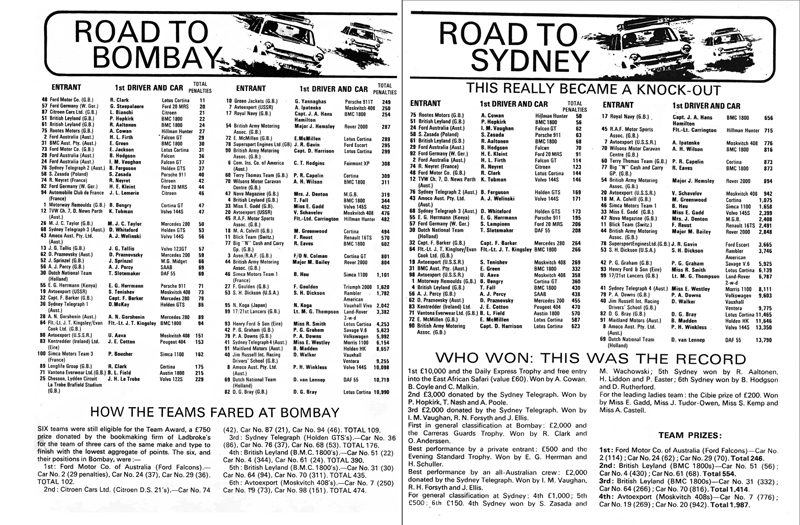

The 1968 Daily Express

London to Sydney Marathon

|

|

The great adventure of the

decade

|

|

In

1967, over a luncheon date, Sir Max Aitken proprietor

of England's

Daily Express newspaper, Jocelyn Stevens and Tommy

Sopwith dreamed up

the idea of a great adventure to try and counter the

despondency felt

in Britain by devaluation of the pound and

anti-establishment feelings

which were to manifest themselves in unrest in cities

all over the

world the following year.

It

was felt that such an event would act as a showpiece

for British

automotive engineering and would result in export

sales in the

countries through which it would pass.

A

committee was set up to organise the event - a 10.000

mile/16.500 km

rally from London to Sydney with a £10.000 first prize

and a £500

trophy to be won. The Daily Express newspaper was to

sponsor the event.

In

order to cover the greatest distance overland with the

most varied

terrain, it was decided to route the rally from London

to Dover, then

by ferry to Calais and then on to Paris, Turin,

Beograd, through

Bulgaria to Istanbul and then to Sivas and Erzincan

and then to Teheran

in Iran, Kabul in Afghanistan, Sarobi in West Pakistan

and on to Bombay

via Delhi.

The

first 72 cars to arrive were to be taken by sea to

Fremantle in Western

Australia where they would be disembarked and then

drive across the

continent to Sydney.

A pair of experienced rally drivers, Jack

Sears and Tony Ambrose were given the task of

reconnoitring the route

to Bombay, making contact with and winning support

from governments,

motoring organisations, police forces and highway

authorities. They

then travelled to Australia where they mapped out the

last 2.800

mile/4.500 km leg.

The P & O

Line agreed to ferry the cars in the S.S. Chusan from

India to Australia.

Over 800

applications were received and 100 were accepted.

Most

of the world's major motor manufacturers entered

teams: BLMC, Ford of

Britain, Ford of Germany, Ford of Australia, General

Motors of

Australia, Rootes, Daf, Volvo, Simca, even Moskvich. A

number of

private entries were also admitted.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

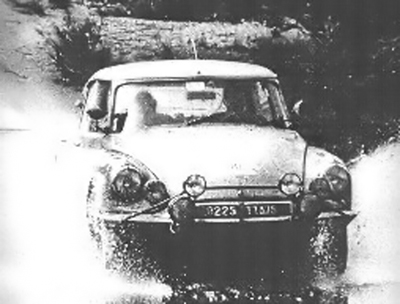

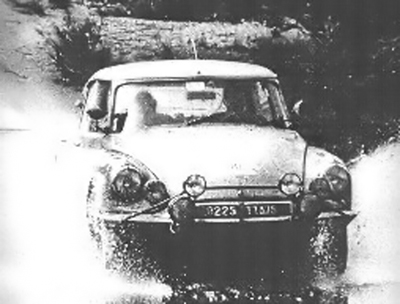

Three CitroŽn DS 21s

were entered; two by the factory crewed by Bianchi/Ogier

and Neyret/Terramorsi and the third, crewed by Vanson,Turcat/Lemerle

was sponsored by the Automobile Club de France.

The three cars were lightly modified compared to the

production

vehicles - the engines were detuned to enable them to cope

with low

ocatane fuels, rear wings featured cutaway wheelarches to

enable rear

wheels to be changed without removing the wings, hydraulic

pipes were

mounted inside the cabin, modified dashboards were fitted with

additional instrumentation and the obligatory `roo bars'.

|

|

On 24th November

1968, at Crystal Palace in London, Miss Australia

flagged away the first car, a Ford driven by Bill

Bengry.

|

|

|

|

|

|

The Marathon had

started! A total of 92 cars were entered.

|

|

|

The first leg of the great

adventure was the run from Crystal Palace in South London to

the Channel port of Dover.

Cheering

crowds lined the London streets to catch the unforgettable

sight of the

most international rallying event yet to be staged.

The

cars were loaded onto the Maid Of Kent ferry and 75 minutes

later,

disembarked at Calais where the reception hall was jammed with

photographers, journalists and well wishers - a phenomenon

that was to

be repeated across the world.

Leaving

at 1 minute intervals, the 98 contestants sped off into the

night

towards Paris. An unexpected hazard on the road to Paris was

thick fog

which at times reduced the cars to a walking pace.

Ice

and freezing fog continued to be a hazard on the early morning

run to

Turin. French customs men decided to enforce currency export

rules and

checked all the crews' money at the Mont Blanc tunnel.

A

number of cars suffered mechanical problems on the Italian leg

but the

three CitroŽns stormed on although one of the teams had their

passports

given to another team in an hotel in Turin which caused some

anguish.

Yet

another hazard awaited the contestants - in Turkey, children

threw

rocks at the cars, denting the bodywork and smashing

windscreens.

By

the time the leading cars had reached Sivas, several

competitors had

dropped out. The first `big killer' stage, the route from

Sivas to

Erzincan lay ahead. 170 miles/272 km of twisting mountain

trail, at

night in driving sleet.

Roger Clark broke

away from the rest of the field, covering the stage at an

average speed of very close to 60 mph/100 kph.

The

competitors had a break at Teheran while the cars were handed

over to

the mechanics prior to the longest single stage of the

Marathon, the

1500 miles/2400 km stretch to Kabul through the Elburz

mountains.

First

into Kabul was Harry Firth in a Holden entered by the Sydney

Telegraph.

Only 33 cars managed to arrive within the allotted time.

The

next stage, Kabul - Sairobi - Delhi, added a new hazard -

dust. Paddy

Hopkirk in his works BMC 1800 lost five minutes on this stage

as did

Roger Clark who still remained in the lead. The well tarmaced

road

through the Khyber Pass and into Pakistan presented few

problems and

surprisingly, both Pakistan and India chose to forget their

political

differences and co-operate in allowing the competitors to

cross the

border that had been closed for the previous three years.

The

last Asian stage - Delhi to Bombay, brought more crashes and

breakdowns

but at last, 72 cars were loaded onto the P & O Lines ss

Chusan for

the nine day voyage to Fremantle. Still leading the field was

Roger

Clark in his Ford Lotus Cortina, second was Staepalaere in a

Ford

Taunus 20 MRS and third was Bianchi in the DS

21.

|

|

|

|

|

The nine day voyage

to Australia gave the competitors the chance to relax

and unwind after the hardships of the previous week.

Many

of the drivers went down with stomach upsets and the

Australian crews

decided it was time to put the frighteners on their

rivals, describing

the perils of dust covered potholes and suicidal

kangaroos.

At dawn on

Friday, December 13, the Chusan docked at Fremantle

and the cars were unloaded.

Local police

booked 26 of the competitors for mechanical defects

and illegal equipment such as sirens and flashing

headlamps.

The hostility

of the Australian police was to continue throughout

the rest of the rally.

|

|

|

The following day,

the cars were lined up for a Le Mans style start at

Perth's Gloucester Park.

Western

Australia's Premier, Mr David Brand and other

celebrities flagged the cars off at three minute

intervals.

Somewhat

ironically, it was the Australians who first had

kangaroo problems although other nationalities had

their share too.

The Marathon was turning into a three-cornered race

between Roger

Clark, Simo Lampinen (The `Flying Finn') in the Ford

Taunus and Lucien Bianchi

in the DS 21. Unfortunately for Clark, his Lotus

Cortina suffered a

piston failure and despite cannibalising Eric

Jackson's car, he dropped

to third place. He made a fantastic recovery however

and managed to

pass Lampinen and push at Bianchi's lead.

Peter

Vanson's DS 21 limped into the Mingary check

point with a suspension failure.

Bianchi however

was still going strong and at Omeo, he had incurred

but seven penalty points against Clark's 12 and

Lampinen's 40.

Bianchi appeared

unstoppable. By now he was five points clear of Clark

who was lying

third. The Taunus then broke a tie rod leaving Andrew

Cowan in the

Hillman Hunter to assume second place.

|

|

|

|

|

|

And then,

disaster...

The race was all

but won by Bianchi and Ogier. Not far

from the Nowra control point, 156 km (98 miles) from

Sydney, with Ogier at the wheel and Bianchi

dozing in the front seat, the DS 21 hit a Mini

head on in a section of road that was supposed to be

closed to the public.

The DS 21 was wrecked and Bianchi was badly

injured.

Paddy Hopkirk

arrived on the scene and promptly threw up any chance

of winning the rally by turning round and going for

help.

It was

rumoured that the occupants of the Mini were a pair of

off-duty policemen who were both `drunk as

skunks'.

Andrew Cowan

went on to win the Marathon in his Hillman Hunter.

Talking with Dutch CitroŽn magazine CitroExpert

(in the January/February 2019 edition), Claude Ogier

observed it is still his belief that the Ďaccident'

was deliberate.

"There was no traffic at all. I was driving in the

middle of the road,

it was a right turn, and then suddenly there was that

Mini. I sent to

the left, there was enough space to pass each other,

but that Mini kept

coming our way. I could not go anywhere, we were just

being rammed.

Those guys in that Mini had four-point harnesses,

which you only had in

airplanes at that time. We did not have them either,

and we took part

in the race! I am convinced that it was intentional,

probably because

of bets that had been placed, which meant that a

British car had to

win. We did not make any more of it, because that

would not have been

useful, but the disappointment was obviously great.Ē

|

|

|

|

The Final

Reckoning

Okay,

so Bianchi's DS didn't win and Neyret was placed ninth

but this

fourteen year old design showed it was a match for

anything else on the

road.

The high

pressure hydraulic system which had been so

troublesome when the DS was

first launched had finally come of age and

demonstrated that it was

utterly reliable, even under the most extreme

conditions imaginable.

Since

we Brits manage to turn defeat into victory (Charge of

the Light

Brigade - Dunkirk, etc.) I feel perfectly justified in

saying that

Lucien Bianchi was the moral winner of this incredibly

gruelling rally.

It

was primarily the size of Bianchi's lead - he had an

eleven minute lead

over Cowan and only 39 penalty points as opposed to

Cowan's 50 - that

tells the true story.

The three CitroŽns were essentially

unmodified - such modifications that were performed

were designed to

increase the range and provide more information to the

occupants and to

detune the engine to enable it to cope with the low

grade petrol

encountered throughout Asia.

The hydraulic system was unmodified apart from

re-routing the pipework

inside the car to protect it and to enable roadside

repairs to be made

more readily.

Many of the

competitors' cars were extensively modified with tuned

engines, raised and reinforced suspension, etc.

There are some

pictures of a replica of the Neyret Terramorsi vehicle

in the Bruno

Jammes PhotothŤque.

|

|

|

|

|

Above the P & O Line S.S. Chusan

Lampinen

and Staepalarae were booked by the police in Victoria

for speeding

after a 75 mph/120 kph chase. The police threatened to

impound the car

at one stage.

Soon

after leaving the Omeo check point, Clark suffered a

broken

differential but, encountering a Cortina by the

roadside, tried to buy

the rear axle. The owner initially refused but then

said `You're Roger

Clark, the English driver, aren't you?' and parted

with his rear axle.

After an 80 minute delay at

the local garage while the axle was fitted, Clark was

once again back in contention.

|

|

|

|

|

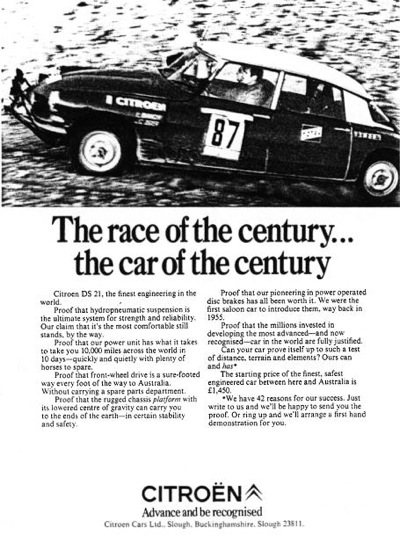

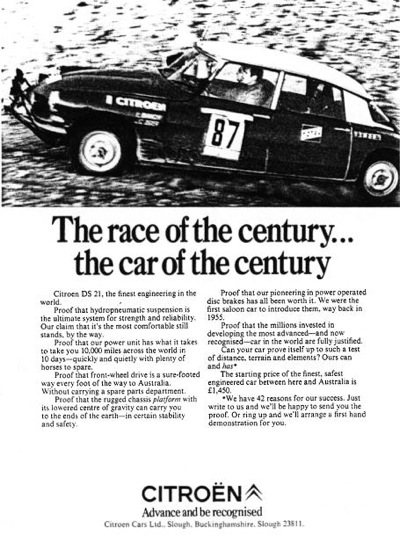

So confident where

CitroŽn Cars Ltd that Bianchi had won the

rally that they put a full page

advertisement in most of the British newspapers

of the day.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Acknowledgments:A

number of people assisted me in this project,

including, in Europe,

Wouter Jansen, John Reynolds and Andrew Minney, and in

Australia, John

Stafford who was absolutely invaluable in providing

the antipodean

perspective and John Waterhouse who provided the two

colour pictures of

Bianchi's car in the Outback and Craig Keller.

The Daily Express was singularly unhelpful, declining

to respond to either e-mails or letters.

© 1996 and 2019

Julian Marsh and 2019 CitroExpert

|

|