CitroŽn

SM

|

|

|

Autocar

w/e 7 September 1974

|

|

Elegant

complexity

10,000 Miles

By Ray Hutton

|

|

|

|

|

The CitroŽn SM can claim to

be the world’s most advanced car. Is all the complication worth the

cost?

After a long-term test which

has

encompassed two different SMs and journeys ranging from long

Continental trips to 50 mph-limited commuting, we believe that it is.

|

|

|

This story really begins last summer when Autocar

entered a

CitroŽn SM in the BRSCC’s first Tour of Britain. Howden Ganley and I

drove it.

Our result was nothing to get excited about; the car had

proved less competitive than we had hoped and more difficult to handle

than we had anticipated. I remember asking Howden what he thought we

had learnt from the exercise. His answer was succinct: “Well,” he said,

“Now we know why people don’t race CitroŽns”.

With hindsight, it was a pretty rotten thing to do to a

fine

car, which, like all CitroŽns had been designed with a “clean sheet”

approach to meet certain specified conditions. Those included the need

for quiet, high speed cruising, a superbly comfortable ride over all

sorts of surfaces, and a very sophisticated power steering system. But

they did not include racing.

In our original road test of the SM (Autocar 10 June

1971) we

described it as “technically the world’s most advanced car”. One of our

intentions had been to find out how reliable its many complex systems

would be under the stresses and strains of competition as well as in

normal use. On the Tour

they had given no trouble and a few weeks later, denuded

of

its roll cage and with the dents knocked out, the car came back for us

to gain further experience with it under more typical road conditions.

It was running well, though both engine and gearbox were

noisier than they had been originally.

From the long-term test point of view the snag was that

very

little was known of this car’s history; it had been prepared as a Group

1 rally car by the CitroŽn Competitions Department in Paris and had

seen action as a practice car for the Moroccan Rally (which an SM won

in 1971). Furthermore, it was not the latest model as it had the

triple-Weber carburetted engine which had been superseded by the Bosch

electronic fuel injection version. CitroŽn Cars Ltd. very generously

agreed to the long-term loan of a never-raced-nor rallied Injection SM

in its place.

It had done 4,000 miles as a press demonstrator; we

aimed to add a minimum of another 10,000.

Actually it could not have come at a worse time. It was

the

beginning of December and the height of the fuel shortage around

London. None of us were using cars for long journeys if we could avoid

it and those who would normally have been so keen to drive the SM were

squabbling over our Renault 5 and Fiat 127. Experience suggested that

we would be unlikely to get more than 15 mpg around town, though even

at that rate its big tank gave it a useful 300-mile range — providing

you could find somebody to fill it up. But then there was the 50mph

limit which succeeded in its intention of boring us away from the

motorways, and at which speed the SM would not run cleanly in fifth

gear. In any case it seemed anti-social to be using a car so obviously

designed for the enjoyment of motoring in those petrol-starved times.

The miles went on slowly.

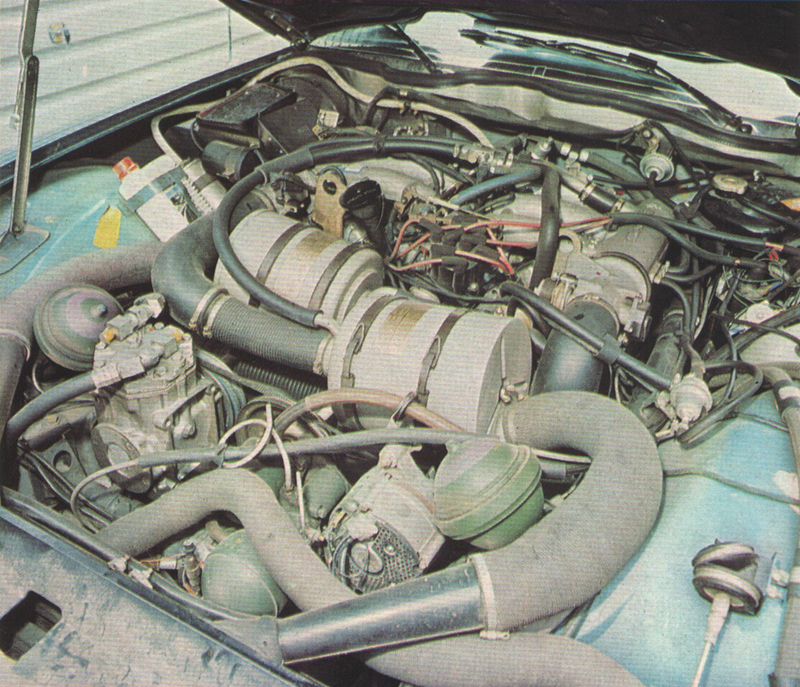

From a driveability point-of-view I am not convinced of

the

advantages of fuel injection. The SM Injection Electronique (EFI) had

excellent throttle response when accelerating and none of the “hunting”

at low speed and idle that is associated with some electronic systems,

but does not have the reassuring shut-off when the throttle is lifted

like an old-fashioned carburettor engine. It had an occasional

light-throttle hesitation. Furthermore, it turned the SM’s already

frighteningly complicated underbonnet scene into a mechanic’s nightmare

with its system of air ducts, filters, intakes and banana-shaped inlet

manifolds. Having spent a frustrating hour removing the six sparking

plugs on the carburettor car (the sixth was totally inaccessible) I was

glad that the fuel injection version did not share its tendency to foul

its plugs in traffic. In fact, cold starting and subsequent drive-away

were always excellent. The rich mixture control is automatic.

Our road test of the injection SM (Autocar 23 August

1973) had

suggested that apart from maximum speed (4 mph up) as a result of

higher gearing, performance was slightly down compared to the earlier

model. Figures taken with our long-term car at 11,000 miles, published

here, show an improvement over the original injection test car in

step-off, though as a whole they are still a little slower than the

first SM that we tested. Such observations are really only of

theoretical interest because the SM is not a car that is bought for

ultimate performance alone.

|

|

Above:

The EFI test car was trimmed in expensive leather. Seats are

comfortable and infinitely adjust able, but they lack side support.

Facia is simple and features multi-purpose warning light system

(inset). The big red light in the centre is additional warning of

hydraulic failure, loss.of oil pressure, or overheating. The button is

to check that these warning lamps are working.

|

|

Performance is in any case remarkably good for a car

that weighs over 30 cwt and is powered by an engine of only 2.7 litres.

Altogether the SM is an odd amalgam of characteristics.

Its

startling, super-streamlined body couldn‘t be anything but a CitroŽn

and its aerodynamic efficiency, shown by its maximum speed and lack of

wind noise, are what one would expect from the flagship of this very

imaginative firm. The Maserati V6 engine on the other hand, emits a

splendid racing growl under hard acceleration and has quite a harsh

feel to it when working hard. Similarly, the manual five-speed gearbox

has a precise “gated” change that would not be out of place in an

Italian sports car, and belies the transmission’s distant location from

the cockpit. Somehow, with such a futuristic appearance a conventional

power unit and transmission seems out of place; it deserves a gas

turbine and fully automatic transmission at the very least.

These things and others, therefore, give the CitroŽn SM

a

truly unique character. It is not everyone’s cup of tea. Certainly it

takes some getting used to, which is why we encouraged anyone driving

it for the first time to do a longish journey which would give him time

to adapt to its peculiarities and also use the car under the conditions

for which it was primarily intended. Not everyone returned convinced.

For me it was a taste quickly acquired, like eating an avocado pear for

the first time: you are unsure at first, come to appreciate its subtle

qualities and then can’t have enough of them.

The thing that needs acclimatization (and can catch you

out

when you come back to the SM from another car) is the very high geared

steering. It is like driving a go-kart; at first one tends to

over-steer and over-correct, and progress is twitchy. When mastered, it

is one of the best features of this remarkable machine. Mechanically it

is one of the most complex of the car‘s systems and its method of

operation is unique. It is perhaps worthwhile to take a little space to

examine what Citroťn’s engineers set out to do and how successful they

have been in meeting the object.

The SM is heavy, and has a substantial front weight

bias; it

has front-wheel drive; and big tyres (205/70 VR 15 Michelin XWX on the

injection version — the same as we used on our “racer“). Power steering

was clearly essential. It needed to be light for low speed manouevring

since the SM is a big car with an unusually long wheelbase. They wanted

to have the degree of positive control that only a racing car with very

high geared steering could attain. Two turns from lock-to-lock was

judged to be ideal, but with the light control envisaged for parking,

would make the steering far too sensitive at high speeds. Their

solution was to build an artificial “feel” that increased with the

speed of the car and they used ideas from aircraft control systems to

achieve it.

So, as the speed increases, the resistance at the

steering

wheel is increased, giving it the feel of an unassisted set-up with the

advantage of very high gearing. An adjunct to this is that the steering

has servo self-centring. At low speed or when stationary this means

that the front wheels automatically return to the straight-ahead

position, though any hand movement by the driver causes a positive

reaction in the hydraulic valve system which then assists his movement

like a more conventional power-steering arrangement. Furthermore since

all the “feel” is artificially created, the steering wheel is very

largelyinsulated from kick-back over bad surfaces and some of the less

favourable characteristics of front-wheel-drive.

|

|

Above:

If it breaks down, call a plumber … Underbonnet view is daunting, with

V6 engine buried beneath injection system and inlet manifolds

|

|

The mechanics of this system have been dealt with in

detail in

these columns (Autocar 21 January 197l). It works exceedingly well and

plays a very large part in the confident and accurate way that this

large car can be rushed through twisting roads like a sports car. Many

of the less attractive characteristics of the front wheel drive layout

are disguised by it under normal conditions, including the understeer

and its tendency to pick up and spin the inside front Wheel. Progress

that seems very dramatic from the outside feels very secure from

within, and as a result one often finds that one has entered a corner

much faster than expected.It contributes to the car’s excellent “hands

off’ straight line stability.

The self-centring makes the car surprisingly easy to

park at

the kerbside, for once a gap has been entered, straightening up is

simply a matter of letting go of the wheel between each backward or

forward manoeuvre. There are a few disadvantages too. Even when used to

it, in town it does need a fairly delicate approach, which not everyone

is able to muster. It is a quirk of the system that it is still a

little too sensitive around the immediate straight-ahead position.

Correct adjustment to the steering wheel’s straight-ahead position is

critical (and quite easily done by moving the rack; a single bolt job).

We found that out on the Tour of Britain when the steering was deranged

by an argument with the Armco at Oulton Park. A bottom wishbone

mounting was slightly bent and I remember driving down the M6 applying

perhaps one-eighth of a turn of lock to keep the car straight; a job

that became increasingly harder on the wrists as the car went faster.

More serious though was my discovery that the very

steeply

cambered roads that are found in some parts of France had the same

effect (with the steering in good order) and that driving fast along

them became physically tiring as one struggled against the steering to

keep the car on a straight course.

I mentioned manouevring a while back. From the steering

point

of view this is easy, but the very wide front and long sloping nose

means that like the DS Citroťns it is hard to judge its not

inconsiderable size (16 ft long and 6 foot wide) when turning in

confined spaces. My colleagues are fond of telling stories about the

many people who have misjudged the gates of the office car park with

DSs. I made the mistake of boasting that I didn’t understand the

problem; I had never had any trouble with them. The very next morning I

confidently swung the SM through the gateway only to hear a sickening

clang. In fact, all I had done was to break off the thick rubber facing

on the bumper that wraps round the nose, but it illustrated just how

close I had been judging things without realizing it. The SM is longer

and wider than it seems.

|

|

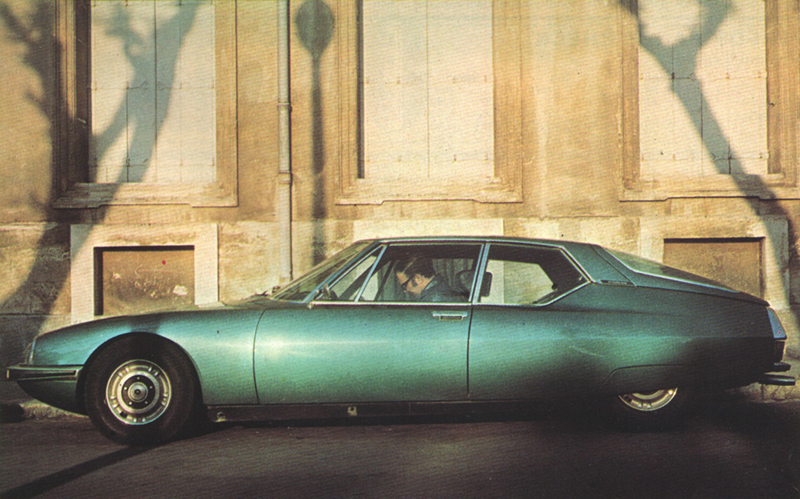

Above: the SM EFI outside the walled

town of Carcassonne, en route for Spain.

|

|

In

another make of car the suspension and ride would be

remarkable. Sufiice to say that the SM uses the well-tried CitroŽn

interconnected hydropneumatic struts which make it self-levelling and

has ride comfort second to none.It has a three position ride-height

adjuster to give it adequate ground clearance for any sort of bad road.

As with the DS and GS, bumps and bad surfaces are ironed

out

with ease, and only hump-back bridges and the like catch the suspension

out. For reasons that are not entirely clear to me, its performance

over cobbles is less impressive, a sort of uncomfortable patter being

set up from the rear wheels. Road noise is high, being particularly

sensitive to bump-thump from cat's eyes.

I took the car to the Spanish Grand Prix at Madrid,

which

involved all aspects of motoring from rock steady cruising at very high

speed on motorways (120 mph is quiet and comfortable; roads, laws and

traffic permitting), to snow-covered mountains in Andorra. Fast main

roads with long sweeping curves are the SM’s forte; for much of France

there can be few ears quicker. On slower, sharper corners its biggest

disadvantage becomes apparent - the amount of roll. The car really

isn’t happy being driven through a series of lacets with verve. No

sooner has the suspension caught up with the car’s attitude for one

corner than it is unsettled again for the next. The result is a lot of

bucking around to accompany the inevitable tyre scrub and a very

uncomfortable time for your passengers, who are not helped by the lack

of sideways location in the seats. In general, it is better to adopt

the rear-wheel drive technique of “straightening out“ corners as much

as possible to keep the roll to a minimum.

Hard acceleration produces a noticeably nose-up attitude

but

under heavy braking the anti-dive geometry reduces the opposite

reaction. I fid the DS-type no-travel brake button very reassuring for

a fast car and the all-disc set up proved very consistent in normal use

except on one occasion when unexpected front wheel lock on a slippery

country road caused me some anxious moments. Out of curiosity I tried

to reproduce this in tests at MIRA and found that after four or fie

repeated heavy stops the rear wheels did have a tendency to jack up and

slew sideways as the fronts locked.Under normal circumstances, however,

the brakes are without fault.

One could not fail to be impressed by the SM‘s

performance on

our trip to Madrid. By the effortless way that it ate up the miles,

with virtually no wind noise and just the dull drone of the engine in

its high fifth gear; the impression from within is in some ways more

like a small aeroplane than a car. There is the feeling of insulation

from the outside world, yet with a solid aura of security and the

confidence of complete control. I was not surprised to hear from

‘CitroŽn that a large percentage of the 400-plus British customers for

SMs use them for long journeys, particularly on the Continent. One such

customer is Mike Hailwood, who has had his SM for three years, yet

previously changed his cars on whim every few months. “It’s nice and

comfortable on main roads — I just like it", he says, confessing that

he doesn’t look after it very well and that it had been reliable

“except when there was no anti-freeze in it last winter - that messed

it up a bit.

Strangely enough, ‘the water system‘ gave me some cause

for alarm on the return from Spain.

Slightly higher than normal water temperature and the

need for

three or four pints of topping up water a day suggested either a leak

(which wasn’t visible) or head gasket trouble. When safely back home it

was found to be the latter - a problem not unknown previously and which

had resulted in a new design of gasket. Otherwise, the 3,200 mile round

trip was marred only by a bad engine-induced vibration,

irritatingly transmitted through the chassis at a steady 4,500 rpm,

which represents just over 100 mph in fifth gear and 80 mph in fourth.

Apart from discouraging cruising at these otherwise convenient speeds,

this was no doubt one reason why several minor bolted-on components

like door and boot locks and one headlamp mounting came adrift during

the trip.

Vibration also tended to cause the adjustable steering

column

to slip to its lowest position. In and out and up and down column

adjustment is only one of the factors which go towards producing a

perfect driving position for everyone. The seats can be adjusted for

height front and rear, and thus for rake as well, while the backrests

are,unusually, hinged half way up instead of from the base. This looks

as if it ought to be uncomfortable but in fact provides the fine

adjustment to get the driving position just right. The thick, soft head

restraints are also fully adjustable. Stuart Bladon has an irrational

fear of headrests and the like and ejected them before even sitting in

the car when he took it to the Geneva Show. A pity, for had he tried

the SM’s, he would have found them most comfortable; both for

supportingthe driver’s neck and as a pillow for the front seat

passenger.

|

|

Above:

The SM is a big car. Its streamlining is good for aerodynamics, less so

for visibility. The suspension is adjustable for height; here it is at

the lowest setting

|

|

The test car differed from our Tour SM in having

leather,

rather than nylon cloth-covered seats. These add a hefty £258 to the

price, but their smoothness only accentuates the lack of sideways

location, and the far from ideal placing of the unusual socket-clasped

Toric seat belts did little to help.

Though a driver and one passenger could travel all day

in the

SM without getting uncomfortable - and arrive fresh at their

destination — carrying four people for any distance is less

satisfactory. The rear seats are well upholstered and nicely

shaped but headroom and, more particularly, leg room are a problem,

though rear passengers’ feet can be tucked under the front seats. In

recognition of this, the front passenger‘s seat has less adjustment

than the driver’s. Even someone of average height feels more

comfortable with the passenger seat near its rearmost point.

One is forced to concede that in terms of packaging, the

SM

does not come out very well. Like many American cars of similar (and

bigger) dimensions it is really only a 2+2. Neither is the luggage

space over-generous. The big spare wheel occupies a great deal of boot

space. We managed to accommodate all our luggage plus typewriters and a

lot of camera gear in it for the Spanish trip, but only by using a

number of soft bags instead of suitcases. The boot leaked. Inside

stowage space for oddments is provided by some useful side bins (in the

doors and at the rear) and a disappointingly small facia locker.

Though it looks very futuristic at first glance, the

facia is

actually quite straightforward. It is possible to adjust the steering

column to the point where the working range of the speedometer and rev

counter are not visible. The third matching oval dial has no less

than l4 warning lights, for everything from indicators to hydraulic

failure and a test switch so that you check that the bulbs are working

in the more important ones. The three smaller gauges at the centre are

for water and oil temperature and fuel, the latter being very vague

(the same system flashes the low fuel warning light on bends with nearly

half a tank left). The heating and ventilating controls are nice to use

and easy to understand; air distribution is good though the heater

isn’t all that powerful. Our car had the optional air conditioning —

pleasant, but £291 extra. On the centre console, trimmed like the facia

with a bronze satin-finish aluminium, is the switch for the electric

windows which are maddeningly slow in operation, the handbrake, and the

radio slot. I was disappointed to hearĽ that cassette players should

not be mounted vertically; we fitted a Radiomobile 330 radio which was

reported on in the issue of 13 July 1974.

Lighting, wipers and indicators are dealt with by

finger-tip

stalks. The bank of six quartz-halogen lights is yet another SM novelty

and they too are self-levelling as well as the inner pair moving with

the steering. The spread of light that they produce is fantastic,

though unfortunately they prove very difficult to adjust

satisfactorily. One of the toughened glass headlamp covers was smashed

by gravillons on my return through France. The wipers — which have two

speeds, intermittent (variable by rheostat) and not fast enough — are,

however, really not up to the performance of the car.

No one would expect a car of this price, let alone of

this

complexity, to make concessions to the home mechanic. Servicing and

repairs are a specialised business for which mechanics are specially

trained. 25 of Citroťn’s 180 British sales outlets are officially “SM

dealers”. During our tenure the sight tube on the big green canister

which contains all the hydraulic fluid never dropped below “maximum”.

Access to oil and water fillers, washer bottle, even the distributor

and alternator is not bad. Checking and topping up the battery is more

awkward and if it needs to be removed it has to be taken out through a

hatch in the right hand wheel arch. Aside from those items mentioned we

had no troubles or failures with the car. Front brake pads needed to be

renewed at 6,000 miles and again at 14,000; at which point it also

needed a new pair of front tyres. These running costs are included in

the accompanying table. To put the overall fuel consumption figure into

perspective, the average for the Spanish trip was 20 mpg. General use,

including commuting, varied between 15 and 19 mpg with an all-time low

for 150 miles around London of 10.5! Overall. the car proved more

economical than the carburettor SM.

Only the privileged few can afford a car that costs

nearly

£7,000. But even leaving price aside, the SM is not for everyone.

Opinions among our testers range from great enthusiasm to “no thanks”.

It is a true Grand Touring car and needs to be used as such. Around

town and in little country lanes it is rather unwieldy and this country

made worse by being left-hand-drive. CitroŽn acknowledge that they lost

a lot of potential customers when plans for a right-hand-drive version

were dropped.

As enthusiasts we have tended to dwell on its technical

marvels but let us not forget that as an attention-getter the SM is

supreme. Even in France it turns heads and in the little villages of La

Mancha in Central Spain the inhabitants treated it with the suspicion

and wonder of something from Outer Space. It is a strange mixture, the

SM. Mechanically ornate; simple in line; beautiful yet functional. A

girl friend of mine described it as “the sexiest car in the world”. I

know what she means.

|

|

Above: How it started. The Group I

carburettor SM on a stage of the 1973 Avon Motor Tour Of Britain

|

|

PERFORMANCE CHECK

|

|

Maximum speeds

|

Gear

|

mph |

kph |

rpm |

|

R/T

|

Staff

|

R/T |

Staff |

R/T |

Staff |

Top (mean)

|

139

|

137

|

224

|

220

|

6,000

|

5,900

|

Top (best)

|

140

|

139

|

225

|

224

|

6,030

|

6,000

|

4th

|

118

|

118

|

190

|

190

|

6,500

|

6,500 |

3rd

|

87

|

87

|

135

|

135

|

6,500

|

6,500 |

2nd

|

59

|

59

|

95

|

95

|

6,500

|

6,500 |

1st

|

39

|

39

|

63

|

63

|

6,500

|

6,500 |

Standing

1/4 mile

|

R/T |

17.1 sec

|

81 mph

|

|

| Staff |

17.1 sec

|

81 mph |

|

Standing

kilometre

|

R/T |

31.0 sec

|

109 mph |

|

| Staff |

31.0 sec

|

109mph |

|

|

Fuel Consumption

|

Overall

mpg

|

R/T

|

17.9 mpg (15.8 litres/100km)

|

|

Staff

|

18.1 mpg (15.6 litres/100km) |

|

|

Acceleration

|

True speed mph

|

30

|

40

|

50

|

60

|

70

|

80

|

90

|

100

|

110

|

Indicated speed R/T

|

33

|

43

|

53

|

64

|

75

|

85

|

96

|

106

|

117

|

Indicated speed Staff

|

30

|

40

|

51

|

62

|

72

|

82

|

92

|

102

|

112

|

Time in seconds R/T

|

3.5

|

5.0

|

7.2

|

9.3

|

13.0

|

16.4

|

21.1

|

25.9

|

31.5

|

Time in seconds Staff

|

3.2

|

4.7

|

7.1

|

9.3

|

12.9

|

16.1

|

21.3

|

26.2

|

33.2

|

|

Speed range, Gear Ratios and Time In Seconds

|

mph

|

Top

R/T

|

Top

Staff

|

4th

R/T

|

4th

Staff

|

3rd

R/T

|

3rd

Staff

|

2nd

R/T

|

2nd

Staff

|

10-30

|

-

|

-

|

-

|

-

|

6.9

|

5.8

|

4.3

|

3.9

|

20-40

|

13.0

|

11.5

|

9.1

|

8.2

|

6.0

|

5.7

|

4.0

|

3.5

|

30-50

|

12.7

|

12.0

|

8.6

|

8.3

|

5.7

|

5.5

|

3.9

|

3.5

|

40-60

|

12.3

|

11.8

|

8.1

|

8.6

|

5.8

|

5.5

|

-

|

-

|

50-70

|

12.1

|

11.2

|

8.8

|

9.0

|

5.9

|

5.7

|

-

|

-

|

60-80

|

13.3

|

12.8

|

9.1

|

9.8

|

7.5

|

6.3

|

-

|

-

|

70-90

|

14.8

|

14.4

|

9.6

|

10.2

|

-

|

-

|

-

|

-

|

80-100

|

15.5

|

14.9

|

10.4

|

13.3

|

-

|

-

|

-

|

-

|

|

|

COST OF OWNERSHIP

|

|

Running Costs

|

Life in miles

|

Cost

per 10,000 miles

|

One gallon of 5-star

fuel average cost today 55p

|

18.1

|

£303.86

|

One pint of top-up

oil average cost todau 29p

|

550

|

£5.27

|

Front disc brake

pads (set of 2)

|

6,000

|

£25.41

|

| Rear disc brake pads

(set of 2) |

12,000

|

£8.99

|

Michelin XWX

205/70VR-15 tyres (front pair)

|

15,000

|

£68.80

|

| Michelin XWX

205/70VR-15 tyres (rear pair) |

35,000

|

£29.48

|

* Service (main

interval and actual cost incurred)

|

6,000

|

£118.00

|

Total

|

£559.81

|

Running cost per mile

|

5.6p

|

Approx. standing charges per year

|

**

Insurance

|

£128.10 |

Tax

|

£25.00

|

Depreciation

|

£712.91

|

Price

when new

|

£6,107

|

Trade in

cash value (approx.)

|

£4,700

|

Typical

advertised price (current)

|

£5,300

|

Depreciation

(over 12 months)

|

£807

|

Total cost per mile (based on cash

value)

|

21.2p

|

**

Insurance cost is for 34 years old driver, with £65 per cent no claims

bonus and with car garaged in Byfleet, Surrey. Subject to

compulsory excess of £200. Named drivers only.

|

* Estimated with the help of Eurocars

Ltd. as typical; repair of blown head gasket at 14,000 miles not

included (see text)

|

|

| ©

1974 Autocar/2015 CitroŽnŽt |

|

|

|