|

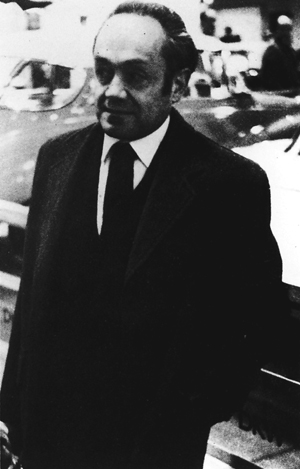

Henri Dargent contributed to

the long and glorious history of CitroŽn

Styling.

A talented model maker, he had

the privilege of being Flaminio

Bertoni's closest working partner

between 1957 and 1964

Forty years on, Henri Dargent

talks to "Double Chevron"

|

|

|

Double Chevron: When did

you join CitroŽn?

Henri Dargent: My father was a

foreman at the Epinettes stamping workshop in

Paris and decided I was going to work for

CitroŽn. I joined the company in 1945 as part of

the Andrť CitroŽn professional training

programme (FPAC).

D.C.: When did you meet

Flaminio Bertoni?

H.D.: The first time was at the

Grande ChaumiŤre academy in Paris, where we were

working on drawing and sculpture from models. We

were introduced for the first time in 1949, at

an exhibition organised by the Association of

CitroŽn Artists. After spending some time in

central tooling, I started work at the design

office on the Rue du Thť‚tre in the 15th

arrondissement in Paris in 1953. 1 began working

with Mr. Bertoni in 1957, at his request.

D.C.: That must have been

a major event for you?

H.D.: Yes, it was really a major

event. I was going to work with a master. When 1

arrived he told me, 'This is a sculptors'

studio. You don't need your drawing board.'

D.C.: Why do you think he

chose you?

H.D.. While 1 was working in

CitroŽn's design office, I was also taking

classes in Applied Arts at the Arts et Mťtiers

engineering college. I wanted to further my

training and get a diploma in engineering. So I

decided to submit some of my vehicle projects to

Mr. Bertoni.

|

|

|

H.D.: He smiled and brushed them aside.

D.C.: What did you work

on in the Bertoni studio?

H.D.: Car models in plaster. We

made life size, scale 1 sculptures. We didn't

make many small models.

D.C.: Did he frequently

intervene, or did he let you get an with

things yourself?

H.D.: It depended, really. It was

a bit of an adventure. I would often leave a

model in a fairly advanced rough form at the end

of the day, and when I arrived the next morning

he'd be changing the model's volumes with his

little hammer!

D.C. : Bertoni made some

magnificent sketches, but the main image we

have of him today is that of the man working

on a model of the Traction Avant. He

pioneered 3D volume modelling. Was this the

most important form in his eyes?

H.D. : It's true that he made

sketches to define a part, but without going

into detail. Only volume counted. He had the

shape he wanted to make in his head, and it was

difficult to get away from it.

D.C.: What was it like

working with him?

H.D.: I admired him. I worked

incredibly hard, and I observed him to

understand how he arrived at the final result.

D.C.: Can you describe

his method?

H.D.: He shaped each model using a

plane, taking into account the way it caught the

light. And he stopped when the result seemed

satisfactory. It was sensual and instinctive

sculpture. But he also knew a great deal about

materials and steel. He always had a reason for

what he did, and he was extremely precise with

technical definitions. Don't forget that he was

a coachbuilder when he was younger. He knew all

about marking out and shaping metal. Bertoni was

a genius he was into everything, and he was a

real workaholic.

D.C.: And when you

presented projects to the management?

H.D.: With him it was a little

like improvised comedy. First, he presented the

models he liked the least, then, at the last

moment, he would say to me, 'OK Dargent, unveil

that one!' It was his way of getting the one he

liked accepted.

D.C.: Did he have any

influences?

H.D.: "He once confided to Robert Opron that

he'd rather go to the zoo than a motor show.

It's true that he sometimes drew his inspiration

from the shape of certain animals. The daring,

futuristic lines of the DS reflects the

"morphing" of a fish and a car. But 1 can assure

you that he paid close attention to other cars.

1 kept some of the notes and sketches he made at

the Paris Motor Show, and they clearly show he

was interested in various things. We're all

influenced by somebody. When Mr. Bertoni was

alone, he focused on himself. But as the team

got bigger, we all influenced each other. In

particular, I'm thinking about the work of Henriques Raba, who won the

Prix de Rome. We can also see Bertoni as the

gifted hand that was able to capture the

aerodynamic shapes Andrť

LefŤbvre was looking for. He felt all of

these things instinctively rather than digesting

them in a scientific way. In my view, Flaminio

Bertoni was truly the greatest in terms of his

sensitivity and feeling for shape."

-

Robert Opron

- Head of CitroŽn Styling from 1964 to 1974.

-

Henriques Raba

- CitroŽn stylist from 1959 to 1962.

-

Andrť

LefŤbvre - Manager of CitroŽn vehicle

styling in the early 1950s.

|

|

Flaminio

Bertoni (1903 - 1964)

The Traction Avant, the 2CV and the DS. These

three exceptional CitroŽn models owe their

existence to the genius and exceptionally

skilled hands of Flaminio Bertoni.

A born artist and a hard worker, Bertoni was no

doubt the first to sculpt body designs rather

than draw them, thus working on volumes more

than on lines.

People say that "il Maestro" created the body

of the Traction Avant "7" in one night in 1933.

He drew the 2CV at the end of the 1940s and

designed the famous "Hippopotamus" in 1947,

forerunner of the DS 19 released in 1955.

Three strokes of genius from one of the

forerunners of modern automotive styling.

|

|